The Largest Waterfall On Earth Is Actually Submerged In The Ocean

Each year, millions of people visit Niagara Falls to admire the roaring water cascading over a series of steep rocky ledges.

Niagara Falls is iconic, but they are not the only impressive waterfalls around. There is another one that is actually located deep beneath the ocean.

It is called the Denmark Strait cataract, and it is technically the largest waterfall in the world. It lies submerged in the Arctic, somewhere between Iceland and Greenland. The waters land in a deep pool of cold water.

The waterfall itself is about 6,600 feet tall, while its waters plunge down a slope of 11,500 feet, which is more than three times the height of Angel Falls in Venezuela, the tallest waterfall on land.

The cataract is roughly 300 miles wide. It is hidden from human sight and advanced oceanographic tools must be used in order to detect it.

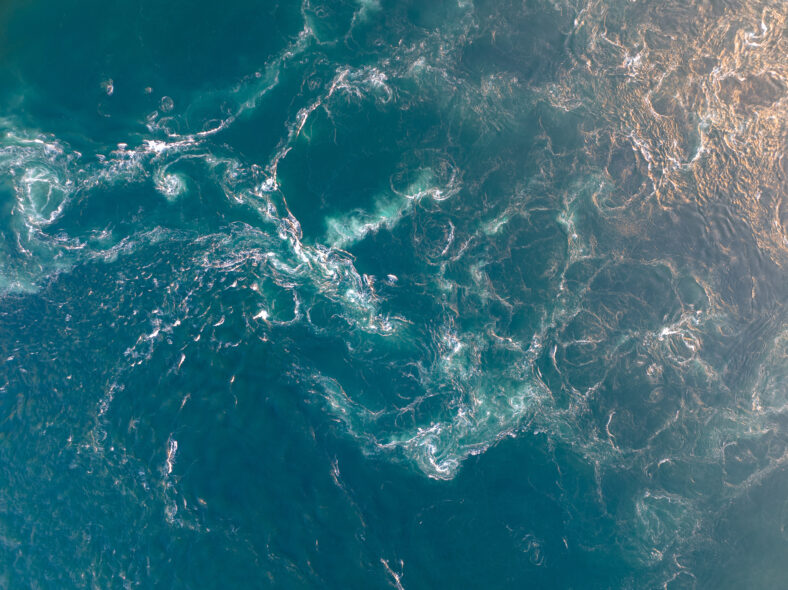

Even though we can’t see it, this enormous waterfall is important for ocean circulation and the regulation of the planet’s climate. It only exists because of the merging of icy water from the Nordic Seas and warmer water from the Atlantic Ocean.

The flow of the cataract’s water moves much more slowly than that of other waterfalls. It has a speed of 1.6 feet per second, while Niagara Falls has a speed of 100 feet per second.

In addition, around 3.2 million cubic meters of water rush over the cataract each second, which is far more than what the Amazon River discharges into the Atlantic Ocean.

The Denmark Strait cataract formed between 17,500 and 11,500 years ago during the last Ice Age. Glaciers reshaped the landscape, carving out the structure of this giant waterfall. It is preserved by temperature fluctuations, shifting ocean currents, and geological processes.

Sign up for Chip Chick’s newsletter and get stories like this delivered to your inbox.

Since it is part of a global system, the Denmark Strait Cataract helps distribute heat, energy, and nutrients across the globe.

The waters come from the Greenland, Norwegian, and Iceland seas and enter the Irminger Sea, a region of the North Atlantic.

It is also where a loop of ocean currents called the thermohaline circulation is located, significantly impacting sea levels, weather patterns, and marine ecosystems.

“What happens here is felt everywhere. The flow creates a ripple effect that connects ecosystems and climates around the globe,” said Anna Sanchez Vidal, a professor of marine science at the University of Barcelona in Spain who led a research expedition in 2023 to the Denmark Strait.

The Denmark Strait cataract is not the only underwater waterfall, but there is no other that can compare to its scale.

It is truly one of a kind and serves as a reminder that many natural wonders we don’t know about exist under our very noses, keeping the world turning in invisible ways.

More About:News